One of our BPM project’s sponsor said at the very beginning, when we discussed the possible project: “my employees don’t need a control, they need help”. I argued at the moment, but later I realized that he was right.

What do we mean when we are talking about controlling a business process? Should we consider paranoid participants suspecting that the ultimate goal is to control them?

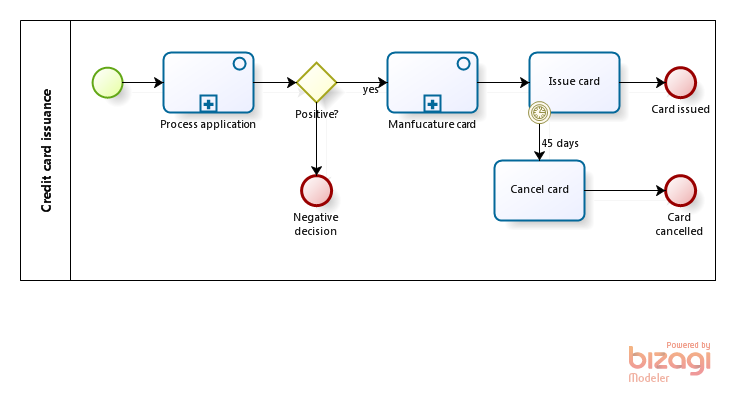

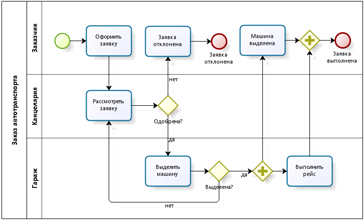

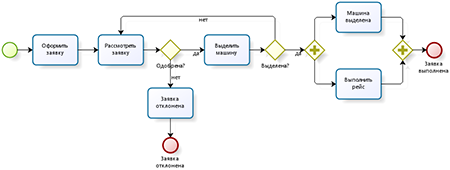

After all, the prevailing view of a process management is this: let’s draw a process diagram and make everyone do what’s written in a box assigned to him. And a manager will get a nice picture: the speed of the corporate machine is running and the amount of fuel it consumes.

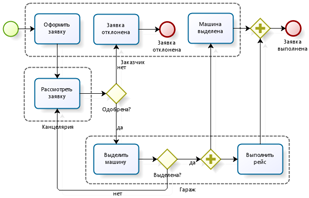

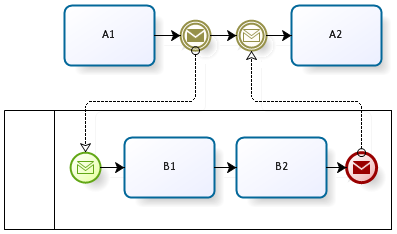

But the real life is much more complicated: it’s always about a network of processes communicating via data, signals and messages. In the absence of computer-aided control it’s people who control these processes: they watch the bills to be paid, the orders to be delivered timely and in accordance with specs, the capacity and materials to be synced with orders accepted. They also deal with non-standard situations: customer revoked the order or paid several bills with one transactions, supplier changed delivery date etc.

These are complicated tasks. Really complicated.

And now comes a business process specialist who doesn’t know how to do anything yet knows how to do it better. But if he only knows how to draw a primitive workflow then it’s no use.

Example:

- A small company reselling “cool stuff”: gadgets, special gifts, designers’ accessories for bathrooms etc.

- A group of processes “Assortment Management”: several employees permanently monitor internet, visit trade shows, get into competitors’ stores looking for new ideas, brands, suppliers. On one hand, due to the business profile, the assortment must be updated by trendy things regularly but on the other the product line shouldn’t be too large, it must be trimmed also regularly.

- These several people assess up to a thousands of candidates per month. The company developed a three-stages filter: first an express assessment made by an expert who throws away most of the income. Then negotiations with vendor, logistics work-out and possible profit estimate. And finally all ideas that passed first two stages are ranged once per month and the top candidates are selected for sample purchasing with the total available budget in mind.

- In parallel, the whole current assortment is analyzed also monthly in terms of diversity, profitability etc.

A lot of aspects are taken into consideration both during selections and assortment revsions. E.g. a number of items within a single assortment group shouldn’t be neither too small (a buyer doesn’t trust when there is no choice) nor too wide (the buyer becomes confused and goes away). The assortment is limited by the physical dimensions: all goods should be placed on the shelf which is limited in size. And other completely informal things like an intuition saying to the expert that particular good is going to be a top-seller.

What can be done here if the path of the least resistance is taken? Well one may automate the assessment with a five-steps process:

- Get the quotation from the vendor

- Find out logistics terms

- Evaluate merchantability

- Assign rating

- Make a decision about sample purchasing

But to start with, as was shown in the previous post, when the budget is constrained the purchase decision may only be made on the basis of the whole set of candidates and no way in the frame of a single candidate assessment process.

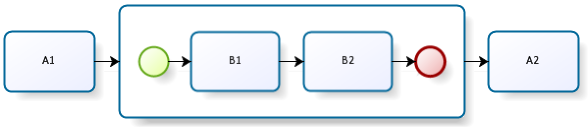

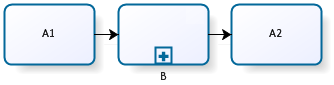

Next, what’s the use of this scheme if all steps are performed by a single employee? This is pure micromanagement. Is it the issue here to control the sequence of tasks? Of course not - the issue is to control the bunch of processes running simultaneously and asynchronously: hundreds of first stage assessment instances, dozens of second stage assessments, selection into and trimming from the assortment. What we need for this task is not a workflow but a complicated enough interprocess collaboration.

People don’t want to be controlled, they need help in controlling really complicated processes.

If you give it to them then there’d be no opposition, people will gladly use a BPM system. Verified by practice.

Yet you’ll need to overcome their distrust on the way - no one at the shop floor a priory expects anything good when “business process” is mentioned. Here is how I break it talking with people:

Imagine that you’ve got a robot assistant. Trouble-free and error-free. It will take the most tediuos, clerical part of your job. You’ll be able to tell it:

- «Robot, make sure this application got the right desk.»

- «Robot, prepare an invoice using these data and post it into accounting DB.»

- «Robot, let me know when we got the payment by this invoice.»

- «Robot, what is the production schedule for this order?»

- «Robot, calculate this client’s rating by our standard procedure.»

- «Robot, watch this order and let me know if it stucks.»

- «Robot, give me all payment requests for tomorrow sorted by contractors.»

- «Robot, what did the boss say last week about this complain?»

- «Robot, the client revoked the order - withdraw it from production if it’s not too late.»

Now tell me - who would not accept such a helper?

Besides the BPM robot is safe because it obeys the laws. Not the Asimov’s law however.

The Laws of BPM Robotics:

- A robot will never be able to do what you are able to do.

- A robot will do only a part of what you are doing.

- A robot will do only a part that you won’t like to do yourself.