Adaptive Case Management was one of the most discussed BPM topics in 2010. It transformed from fuzzy marketing noise into a more or less consistent concept over the past year.

Why “more or less”? Because even the authors of “Mastering the Unpredictable” - probably the most authoritative book on ACM to date - say in the preface that there is no consensus among them, so the book in essence is a collection of articles. Nevertheless there are more similarities than differences in their positions, hence the consistent concept.

Positive Side of ACM

ACM extends the idea of process management into areas that were tough so far: processes a) rapidly changing and b) essentially unpredictable.

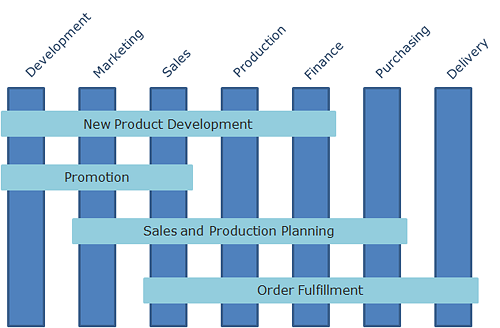

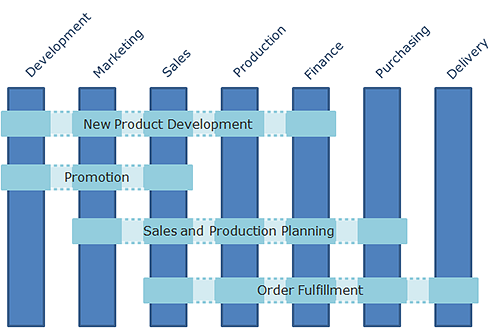

Re-engineering once emerged as the idea of managing business via processes that were perceived as once yet very carefully planned procedured. Life has shown the limited applicability of this concept. It turned out that end-to-end and cross-functional business processes - that is, processes presenting the greatest value in terms of bottomline figures - are a) too complicated to program them in one iteration, and b) changing more rapidly than we are able to analyze them by traditional methods.

As soon as these concerns where perceived BPM appeared in its current form - as a discipline that combines managing business by processes and managing processes themselves i.e. their execution, analysis and optimization within continuous loop. Executable process diagrams improved communications between business and IT opening the way to deal with complex processes; rapid prototyping via BPMS and agile project implementation allowed rapid business processes changes.

Exactly how rapid? We have reached a three-week cycle in our projects which I believe is a good result taking into account the inevitable bureaucracy of release management, testing and production system upgrade control.

But what if this is not enough - if changes to the process should be introduced even faster? Or more likely if a process is so compicated that we repeatedly find that some transition or activity is missing in the diagram?

And here is the final argument in favor of ACM: what if the process is fundamentally unpredictable? Examples: a court case, the history of a medical treatment or technical support dealing with user’s issue. You can’t plan activities here because tomorrow will bring new actions taken by the opposing party at trial or patient’s new test results. It’s even hard to call it a process because process implies repetition, yet no two instances of these “processes” are identical.

These are standard ACM examples. I would also add the no man’s zone between processes and projects e.g. construction work. In a sense, construction of a house is a process because it consists of simiar activities. But at the same time, no construction work goes without troubles and complications which make each object a unique project.

Or let’s consider a marketing event: there is a template indeed but each particular event is peculiar. Same for new product development… there are many such half-projects/half-processes in every company.

What Shall We Do With Unpredictable Processes

If you can’t foresee then act according to the situation. We must give user the ability to plan further actions for himself, his colleagues and subordinates “on the fly”, as the case unfolds.

Luckily the user in such processes is not an ordinary homo sapience but so called knowledge worker. A doctor (recalling House M.D.), support engineer or construction manager - any of them could write on a business card:

John Smith

Resolve issues.

These are people trained to solve problems and paid for this job.

How the problem of volatile and unpredictable processes was approached so far:

1. By editing process scheme by business users on the fly.

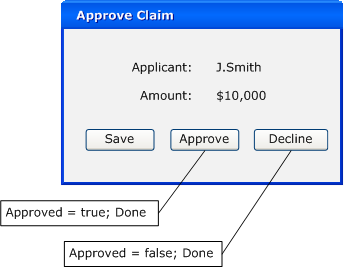

For example Fujitsu Interstage BPM lets authorized users edit the schema of a particular process instance right in a browser. And even more: the modified scheme can be later converted into a new version of the process template. But it turned out to be too complicated - users simply don’t use this functionalty. Keith Swenson says on the matter: “Creating an activity at runtime needs to be as easy as sending email message; otherwise, the knowledge worker will send email instead.”

2. By ignoring the problem: there is software automating case work but it doesn’t operate in terms of processes.

For example you can create a folder in the ECM for each case and upload documents, attach tasks and notes. Or you can treat a case as a project and draw a Gantt chart. But both options won’t give process monitoring and analysis and most importantly - the knowledge of what tasks a particular type of cases consists of will not be accumulated and reused.

ACM inherits BPMS approach to process execution, monitoring and analysis but replaces “hard” templates with “soft”: ACM template doesn’t dictate what should be done but rather prompts what the user could do in current situation. The user may reject these clues and pave his own way. He may use more than one template or instantiate a case from scratch and not use any template.

Graphical process diagram is thrown away and replaced by a tasks list (tasks may be nested). Apart from the tasks list a template defines the data structure: entities, attributes, relationships.

There is no more business analysts and business users: it’s assumed that users create templates themselves and organize them into a library, thus making available to others.

So far so good but I have some concerns about this proposal.

Concern 1: Technology Instead of Methodology?

ACM advocates (or maybe only the most radical only) seem to believe that more advanced technology is all what organizations need to become more efficient: BPMS is outdated but ACM is the solution.

I don’t know… maybe I’m too unlucky but the business people that I meet are indifferent to technology, at best. Techies are speaking about how a new technology works but business people are only interested in what they will get. Productivity increase and processes transparency sound good but how will they affect the bottomline figures?

The bottomline result of a BPM initiative depends on two things: 1) quality of proposed solutions - how efficient is it in managing and optimizing processes and 2) what process was selected for the initiative. Typically, an organization has a small number of processes or just one process which is a bottleneck. Improvements in this process directly affect the company totals while any other improvements affect them at a minimal degree.

If your BPM consultant is professional enough then the first component is secured. But the problem is that the second component of success is beyond his responsibility.

And as a matter of fact, it’s beyond anyone’s responsibility. Business consultants generally know what to do (which processes to deal with) but they have little knowledge of the process technology. BPM consultants, by contrast, know how to do, but don’t have a clear vision of what to do. No system (BPM system is no exception) can establish the goals for itself - it can only be done at super-system level.

After recognizing that there is a competence gap some time ago, we developed the value chain analysis and productivity gap identefication methods to be applied before the BPM project starts. The project takes about a month and results in clear vision of where the BPM initiative should be targeted for best results and what these results shall be.

Getting back to the ACM: it seems that it discards process methodology along with process diagrams. Process analysis skills and process professionals are not needed any more because knowledge workers are so knowledgeable that they know how to do the job better than anyone else.

Maybe they do but let me ask: better for whom - for the company or for themselves?

I am afraid that orientation to the customer doesn’t come automatically. I’m afraid that knowledge workers as well as clerks engaged in routine work tend to create comfort zone for themselves rather than clients. I believe there is still much to be done in process methodology and promising new ideas - e.g. the Outside-In approach - have yet to become common practice.

ACM proponents criticize the “process bureaucracy” - business processes change approvals and other regulations. Bureaucracy is certainly bad… but it’s even worse without it. I don’t believe in empowerment as much as ACM people do and I don’t trust that knowledge workers will self-organize and the library of case templates and business rules will emerge magically. In my opinion, this is utopia. There must be strong leadership and process professionals trained to analyze company’s activities in terms of benefit to the customer, quality and cost.

In his last interview to Gartner analysts process guru Gary Rammler criticized BPM for the lack of business context:

“I think there is only one critical condition for success that must exist - and that is the existence of a critical business issue (CBI) in the client organization. If there is no CBI (hard to believe) or management is in deep denial as to the existence of one, then serious, transforming BPM is not going to happen. Period. There may be misleading “demonstrations” and “concept tests,” but nothing of substance will happen. How can it? Serious BPM costs money, takes time, and can upset a lot of apple carts, and you can’t do that without an equally serious business case. I guess you could argue that a second condition - or factor - is that the internal BPM practitioner is about 70% a smart business person and 30% a BPM expert. Because the key to their success is going to be finding the critical business issue, understanding how BPM can address it, and then convincing top management to make the investment. I guess those are the two conditions: an opportunity and somebody capable of exploiting that opportunity.”

I’m afraid that neglect of a process methodology in ACM will result in ignoring this promising technology by business.

Concern 2: No Programmers?

ACM assumes that not only business analysts are not needed but programmers as well.

Sure it would be great. BPMS vendors try to reduce the need of programmers in business process implementation, too.

Reducing is OK, but eliminating them completely?

Simply replacing the process diagram with the task list probably isn’t enough because there still are:

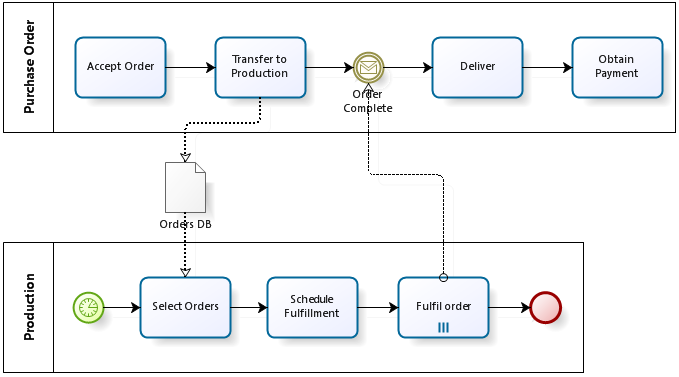

1. Process architecture.

When dealing with process problem the most difficult is to figure out how much processes are there and how do they interact with each other - for an example, please refer to my “Star Wars” diagram. If you did that then the remaining job - internal process orchestration - is no difficulty. If not then whatever you do with rectangles and diamonds within the process, it won’t work well.

Cases are no exception - one have to set up the architecture first. And I don’t believe that a business user without analytical mindset and not trained in solving such problems will do the job. And without that, there will be chaos instead of case management system.

2. Data architecture.

ACM advocates stress the critical importance of data constituing the case context. Arguably, for BPMS process is primary interest and data is secondary while for ACM it’s vice versa.

I do not agree with this - in my view, the process is a combination of the model visualized in a diagram, structured data (process table in the database) and unstructured documents (process folder in ECM) where all parts are equally important.

But anyway - they recommend first and foremost to determine the nomenclature and structure of the entities in your problem. Excuse me for asking, but who will do the job - a business user?

Once again: I don’t buy it! Data structures analysis and design has been and remains a task for trained professionals. Assign it to an amateur and you’ll get data bazaar instead of data base, for sure. Something like what they create with Excel.

3. Integration with enterprise systems.

Well, everyone seem to agree that this will require professionals.

So where did we come? To bureaucracy once again, this time the IT bureaucracy. It’s evil but inevitable eveil because the chaos is worse.

Concern 3: Two Process System?

Here is the question - how many process management systems do we need (assuming that cases are processes, too): two (BPMS and ACM) or one? And if one, how shall it be developed: by adding ACM functionality into BPMS or by solving all range of process problems with the ACM?

ACM proponents (well, at least some of them) position it as a separate system - they want to differentiate ACM from BPMS technology.

They argue that BPMS tries to “program” business but this is impossible in principle when dealing with unpredictable processes. Therefore BPMS is no good and we need a different system - ACM.

It reminds me something… got it: a new TV set commercial! “Just look at these bright colors and vivid images! Did you ever see something like this on your old TV?” - Of course I didn’t… But wait! Am I watching your commercial and see these bright colors and vivid images right on my old TV set?

Same here: of course, unpredictable processes can’t be programmed by a stupid linear workflow. ACM proposes more advanced way to program them, but still it’s programming. And who said that BPMS can execute only stupid linear worflows?

BPM allows to model much, much more than linear workflows. Citing Scott Francis -

“The BPM platforms that I’ve worked with are Turing Complete. Meaning, within the context of the BPM platform, I can “program” anything another software program can do.”

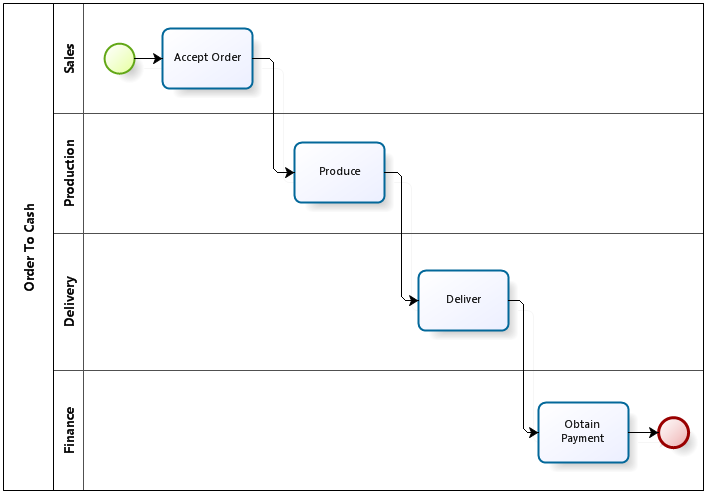

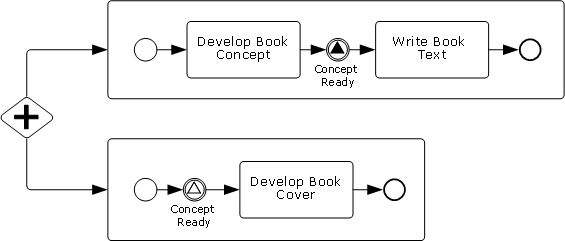

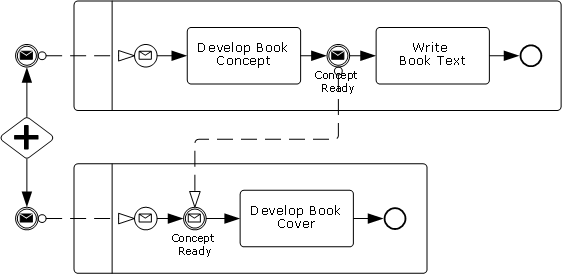

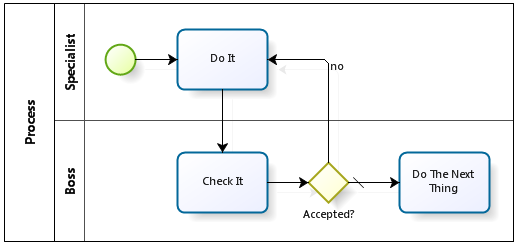

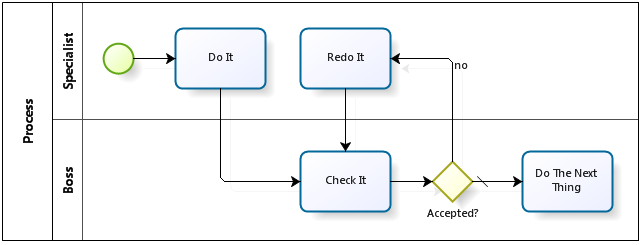

For example, one can model a state machine in BPMN which is presumably the most adequate representation of a case. Besides there are ad-hoc sub-processes that allow a user to choose which tasks to schedule for a particular process instance. The combination of a state machine and ad-hoc sub-processes serving transitions between the states produces something quite similar to the case.

Apart from that, stay away from micromanagement or unpredictability will hunt you everywhere.

Existing BPMS lack the ability to add a new task to the ad-hoc subprocess by one click (remember: it shouldn’t be more difficult than sending e-mail). But it seems to be fairly easy to implement. Not harder than BPMN transactions compensation, anyway.

And there is also “delegation” and “notes” functionality in the BPMS which help making a process less rigid, too.

Some ACM supporters believe that existing BPMS with their process diagrams are outdated - arguably, if ACM can manage unpredictable process then it’ll be able to cope with traditional processes for sure. But the majority seems to recognize that both management of traditional and unpredictable processes are vital.

Besides, there are processes that can be partially modelled but some other parts should be managed as cases. For example, a medical treatment is a typical case but specific test is a process that can be well-defined. This is the argument for a single system able to manage traditional predictable processes, cases and arbitrary combinations of both. And chances are that this system will be developed on the basis of existing BPMS.

Such ACM-enabled BPMS would provide some additional bonuses not mentioned above:

Bonus 1: BPM During All Stages of the Organization Lifecycle

Applicability of BPM is limited today even in regard to predictable processes: small companies simply can’t afford a business analyst and consequently BPM. This mines a future problem: with the company growth the process problems will pile up until falling down one day.

ACM-enabled BPMS would be a great solution to the problem: a small company or startup may work with cases only initially and then, as it grows, the organization structure develops and more clerks coming, a company will be able to transform seamlessly the patterns accumulated in cases into formally determined process diagram, optionally preserving the desired amount of unpredictability.

For the BPMS vendors it’s an opportunity to enter the market of small and medium-sized companies by offering a product falling into office automation category, not a heavy-weight enterprise platform as today. Support of cloud computing would additionally contributed to the success indeed.

Bonus 2: Artificial Intelligence

I do not trust that business users are willing and able to organize a library of template cases. I believe it’ll end with something similar to a bunch of Excel files. How many people are using templates in Microsoft Word, by the way? It’s a nice and usefull thing yet nobody cares.

More promising for me is the idea of implementing elements of artificial intelligence in ACM:

- To start small, a simple advisor can be implemented like the one at online bookstores saying “people buying this book also bought…”.

- More sophisticated implementation may take case data into account. For example a tech support case may suggest one tasks set or another depending on the service level of the current customer.

In essence, the system treats the whole set of case instances of a certain type as a mega-template.

Automatic analysis of the mega-template can be supplemented with manual ratings so that the user would receive not just a plain list of tasks that were performed at the similar situation but the list marked with icons saying e.g. which tasks are recommended.

Conclusion: Thank you!

ACM enthusiasts are doing the great job: they investigate the possibility of expanding the process management into previously inaccessible areas. Sincere thans for this!

Marketing considerations force them to differentiate from “close relatives” BPMS and ECM and to position ACM as an independent class of software. It seems to me that this is irrational both from technology and methodology perspective and it’s unlikely to succeed.

There was a similar story in IT history. Once relational databases have become mainstream a number of works appeared, calling further: post-relational database, semantic databases, non-first-normal-form databases, XML databases… They contained generally fair criticisms of certain aspects of relational database technology. But relational databases proved to have solid potential for evolution: missing functionalities were implemented one way or another, thereby putting alternatives into niche areas.

So here is my prediction for ACM: it won’t become a new paradigm but a new BPM feature that will expands its applicability significantly.